The first water I ever floated in was probably the North Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Hawaii. My two brothers and I were all born in Honolulu Hospital. Although a military family, we didn’t live on base. We lived in a small house in a local neighborhood, which I only remember in the form of plentiful stories. The local Hawaiians, our neighbors, helped the poor, deserted Army wife raise her three kids while her husband was off in Vietnam. We were born there, so we were dubbed kama’aina (native Hawaiians), although we tended to stand out.

However, even if my first experience with water was something so majestic, so primal, as the ocean, the first time I remember swimming, is in our backyard pool in Alabama.

Our house was on a dirt road, and had a sprawling back yard with a big strawberry patch, a chicken coop, and woods that went on a ways. Summers were hot and dusty, with no air conditioning.

We lived in that pool.

There was no formal education to it, no swim lessons at the Y, we just jumped in and taught ourselves. As Mom puts it, we ‘discovered our natural buoyancy at an early age’. There was adult supervision, sure. Dad, who was a medical officer in the Army by then, but had started out as an engineer, was making and installing concrete tiles in a patio around the pool (which I think was previously surrounded by just more dirt), so he would keep an eye on us as we cavorted.

The pool had a level shallow end, which, after ten feet, sloped down to a deeper end where you could dive.

I would have been four or five when I first started spending all my time in that pool. (Like, all my time. There was a point at which I was spending so much time submerged, that my hair never completely dried, and it was all cut off because of the constant mildew smell.)

I was supposed to stay in the shallow end at first, but there was this one time I didn’t.

Not necessarily on purpose.

I was too close to the edge of the deep end, where the slope began. Having taken one step too far, I found myself in a position where I couldn’t keep my head above water, but I also wasn’t heavy enough to stand on the bottom. My toes would brush the surface, but rather than allowing me purchase enough to scramble back to the safety of the shallow end, it just pushed me further away. My as-yet-insufficiently-discovered buoyancy worked against me.

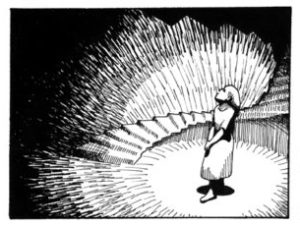

So I drifted just under the water, my hair (not yet reduced) floating above me in swirling tentacles. Below me, and deep into the mysterious unknown of the deep end, the light, fractured by ripples above, raced around the bottom in schools of glowing, glass fish. It was so pretty.

Reaching for the bottom with my toes was useless, so I stopped doing that. Waving my arms didn’t get my head above water, so I stopped doing that. Realizing that the issue of breathing would have to be addressed in the near future, I focused on that instead.

You can’t breathe water, so despite the growing urge to do so, I didn’t open my mouth to draw it in. I knew that much. Instead, I focused on that urge itself. I experimented with it. I pulled my diaphragm down, as if I were breathing, and let it back up again a few times and found this calmed the urge to inhale somewhat. Was there any reason that wouldn’t work forever? I could only try and see.

And so I hung there, suspended in between, both too high and too low, a state which would resonate throughout the rest of my life, until the whole thing ended in a confusing jumble of pain and broken light.

I was told later that my father saved me from drowning by yanking me out by my hair.

I was convinced at the time that I had almost figured out how to breathe underwater, and he ruined it.

Leave a Reply