Alas Uncanny Magazine did not find this to be a good fit with their Disabled People Destroy Science Fiction issue…

Bodies. When you own a healthy body, it’s invisible to you most of the time. You don’t have to think about grabbing a cup of tea. You desire tea, and find the cup at your lips. Effortlessly. Invisibly.

I lost my left shoulder to cancer, an incredibly rare chondrosarcoma. Through some very talented, innovative, well-nigh unique surgery, I was able to keep the arm and hand. But I now have a (3D printed!) metal hinge in my body (an endoprosthesis!) where the scapula used to be. All the subtle, useful bits, like the rotator cuff and half the clavicle, were removed because they were too close to the tumor. Muscles that remained, going as far down as my waist on that side, were pulled up from their normal places and wrapped around the endoprosthesis like a burrito to attach it firmly to my torso. I can’t use the prosthesis to raise my arm, or extend it, or any other shoulderly things, but it holds my arm on. So, although I had to prop my computer in my lap (because I can’t keep my left arm at table level under its own power), and arrange the pillows just so, I have typed this just fine with two hands. I can still write.

I’ve mostly adapted. It’s been exactly a year since the surgery, and I find I can figure out how to do most things. Although some of them I choose not to do in front of people because they require strange contortions and take three times as long as they used to. Some things are just beyond me. What remains of the left arm isn’t rated for anything heavier than 5 pounds.

I stare wistfully at heavy boxes on high shelves.

(In truth, if no one is looking, I will reach up to the elusive box with my right hand, and inch it off the shelf by wriggling my fingers beneath it. Back and forth. Then, when it’s almost over-balanced off the edge, I’ll tip it down onto my shoulder, holding it steady with my head. Clasped between my head and arm, I’ll bobble it over to a table and bend down until I can shrug it off and push it away. If it’s not too heavy. Or too fragile. And if I really need it right then, more than I mind the bruises.)

My goal is for my body to be invisible to me again. I’m tired of looking at it all the time, figuring out the angles and logistics of making and drinking that cup of tea. I would rather just do it. Effortlessly. Invisibly.

As a writer, I’ve been watching myself go through this recovery process. The desire for a return to invisibility has given me a good hard look at what I was taking for granted before, and I’ve decided the body is an illusion. A persistent, well-maintained illusion, that the brain uses to interact with the outside world. So really, there are two bodies. The meat one and the virtual one. That’s why, when people lose a limb, they can still feel it. The meat one may have changed, but the virtual one hasn’t.

When I was first able to start moving the arm, six weeks after the reconstruction, I would try to do things with both hands, automatically, and the left arm would just fall or flop or unbalance everything. Or not move at all. I would be surprised and frustrated every single time. The inconsistencies between the meat arm and the virtual arm were a constant source of disappointment.

So I mentally disowned the arm entirely. I couldn’t update the virtual arm, so I deleted it. I mentally amputated the arm so I could start over. I was a one-armed person. It cut down on the frustration immensely.

Then I started building it back up. If I had a little extra time and energy, I would ‘allow’ the left hand and arm to try to do things. As I found out what it could accomplish, I would slowly build up the new virtual arm and integrate it more into my daily life.

My physical therapist, I think, is fascinated with it. Every time I go in, there is a new, wide-eyed intern following along.

The therspist says to try to lift the arm. I will never lift the arm again, but I still hold out hope of getting more stability, so I try. He holds it a different way and says, okay try to rotate it outward.

And I try. Really hard. I imagine the arm moving, and I’ll have muscles bunching and pulling all over my body that have nothing whatsoever to do with my arm. Like I’m trying to rotate my left arm with my right big toe. And then something will flash or shudder somewhere in my underarm.

Encouraging, the physical therapist says, “There! Did you feel that? Do it again. Imagine reaching out.”

And the freaked out muscle fiber jumps again. We don’t even know which muscle it used to be, everything’s been so rearranged, but after two weeks of trying to activate it, I can get it to contract smoothly and with more control. Who knows what that little fiber will be capable of in another year?

Mechanically speaking, there’s nothing in my shoulder that resembles a shoulder. But there are dribs and drabs, scraps and scars, chunks of meat, that we are trying to repurpose. As I rebuild the virtual arm, my brain is reaching out through abandoned nerves, finding out what they can do, and rewriting them into new movements, new activities. Some of which never existed in the first place. Because the nature of the joint has changed, it can bend frontward and back, in a sort of flapping motion, a little farther than it used to. Is it useful? I don’t know. But it’s already being worked into the virtual model, because I find myself doing it deliberately when I’m getting dressed, without thinking about it ahead of time.

I drive with one arm now. Sometimes the left hand will help out by stabilizing the steering wheel from where it’s sitting in my lap, but that is all it’s good for. The surprising part about relearning how to drive with just the one arm is its similarity to moving my own body in its new conformation. There were new sequences and pathways that had to be adjusted. Driving used to be effortless. Invisible. It’s becoming so again relatively quickly.

I came to realize that the car was every bit a part of my virtual body as my arm was. I didn’t have to think about the car to drive it. I just had to think about where I wanted to go, and the brain would trigger whatever pathways were necessary to get me there. There’s a virtual car connected to my virtual body.

What else fits that category? The computer keyboard, for one. I don’t think about hitting the keys when I’m typing. I just think about the words I want to have appear on the screen. As I type this, I’m conscious of how my mind has generated that virtual keyboard. I type without looking, because muscle memory tells me that this series of impulses generates an ‘e’, and this series generates an ‘h’. As though each symbol existed in my mind as solidly as my own conception of my limbs and fingers. There are letters attached to my virtual body, right there along with the car.

Maybe, given enough training and expertise, this applies to any tool. When you first start using a new tool, it isn’t a part of you. It’s just your meat body touching things and making them go. But eventually, the virtual body becomes so familiar with the use of the thing, that it incorporates it into itself. The piano. The hammer. The paintbrush. The scalpel. The sword. The fighter plane. The prosthetic leg.

The starship.

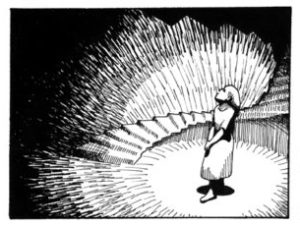

Our tool-using monkey brain is so greedy, snatching up new virtual pieces and sticking them to itself our whole lives, a subconscious Katamari Damacy. When we think of it at all, we think of our virtual self as being roughly the shape of our meat self, but the truth of it is that our virtual selves are vast and complex, operating in more than three dimensions, slapped together like Swiss army knives, bristling with skill sets.

I’ve started back at aikido, a martial art. I had trained for about 15 years on and off before the cancer. I find myself back on the mat with very low expectations, and a body much more brittle. I’ve been pleasantly surprised. Rather than destroying one’s opponent with brute force, aikido is about instinctively understanding another person’s movement and balance so well that you can manipulate it with minimal interference. Since I can’t wave my left arm in dramatic arcs anymore, I find myself closing the distance, refining my position, and throwing very surprised attackers with a well-timed shrug. (Thankfully I can still shrug. Without a way to physically manifest my natural cynicism and ambivalence, I fear this essay would have been much more of a diatribe.)

In training, we talk about reframing the interaction between attacker and attacked, uke and nage, as a collaboration rather than a conflict. You are not being attacked so much as ‘given energy’ which you can choose to use as you like. In the context of the virtual body, in aikido, I wonder if it’s a matter of the ever-acquisitive mind reaching out and using other people’s meat bodies as its own tools, however briefly.

I had trouble getting around to writing this at first. I’m still very angry about how my once strong, dependable shoulder has turned into this crumpled thing, so I didn’t want to give it credit for giving me this insight. It hasn’t been punished enough yet for such an intimate and unforgivable betrayal. After all, it tried to kill me. But it turns out I can be sincerely furious and grateful and appreciative at the same time. The damage extends to about a sixth of my meat body, but, I’ve come to realize, when compared to my virtual body, it’s almost insignificant.

It has changed the way things look to me. When I watch my friend’s three-month old baby flail, I’m seeing her learn to use her first tool, her own meat body. The first of many tools.

So now, when I think about fictional humans, either with new, strangely articulated bio-engineered limbs, or high-tech prosthetics, or plugged into whole structures or cities, I no longer wonder if it’s possible for the human mind to adapt to such things. I know it is. The brain, in its mysterious and powerful way, will find its way to it, like water flowing downstream. All it needs is a connection, feedback, and purpose. Whether the connection be as direct as a nerve, or ephemeral as a touch, our minds can use it to extend the virtual body. I theorized about it in stories before. Now I’ve watched it happen, from the inside.

It’s what we do as humans.

The irony will be that when we’ve invented and incorporated these new miracles into our virtual bodies, into our very identities, we won’t be able to see them anymore. They’ll be effortless.

Invisible.

March 16, 2018 at 3:52 pm

what a wonderfully insightful collection of thoughts. I hope that your virtual body can continue to move forward in partnership with your meat body.

March 18, 2018 at 5:39 pm

Overcoming the pain and the betrayal of one’s own body is beautifully articulated here. (Yet, not that the anger doesn’t rise up daily with the frustration of trying to do ordinary tasks!) Mind over body does work in remarkable ways such as going through the excruciating pain of childbirth yet the emotion of “what the hell is happening??!!!” can give way to the feeling of “I can’t do this!” Which I am sure you must have felt throughout your cancer journey. Admirably, you have found a way through.

Unfortunately , a healthy mind and body is something we take for granted until it’s compromised or destroyed. Coming out of events as simple as a bad cold or the flu make me appreciate the gift of good health…..but then I gradually take it for granted once again.

Reading your entry gives me pause to realize no matter the pain in our lives, it’s a choice to overcome or be defeated and let it define us.

Thank you for sharing your experience.